Michelle Dempsey, Curatorial Assistant

“It is rather blasphemous to leave a garden between June & Oct,” wrote Edith Wharton to Louis Bromfield in July of 1932.

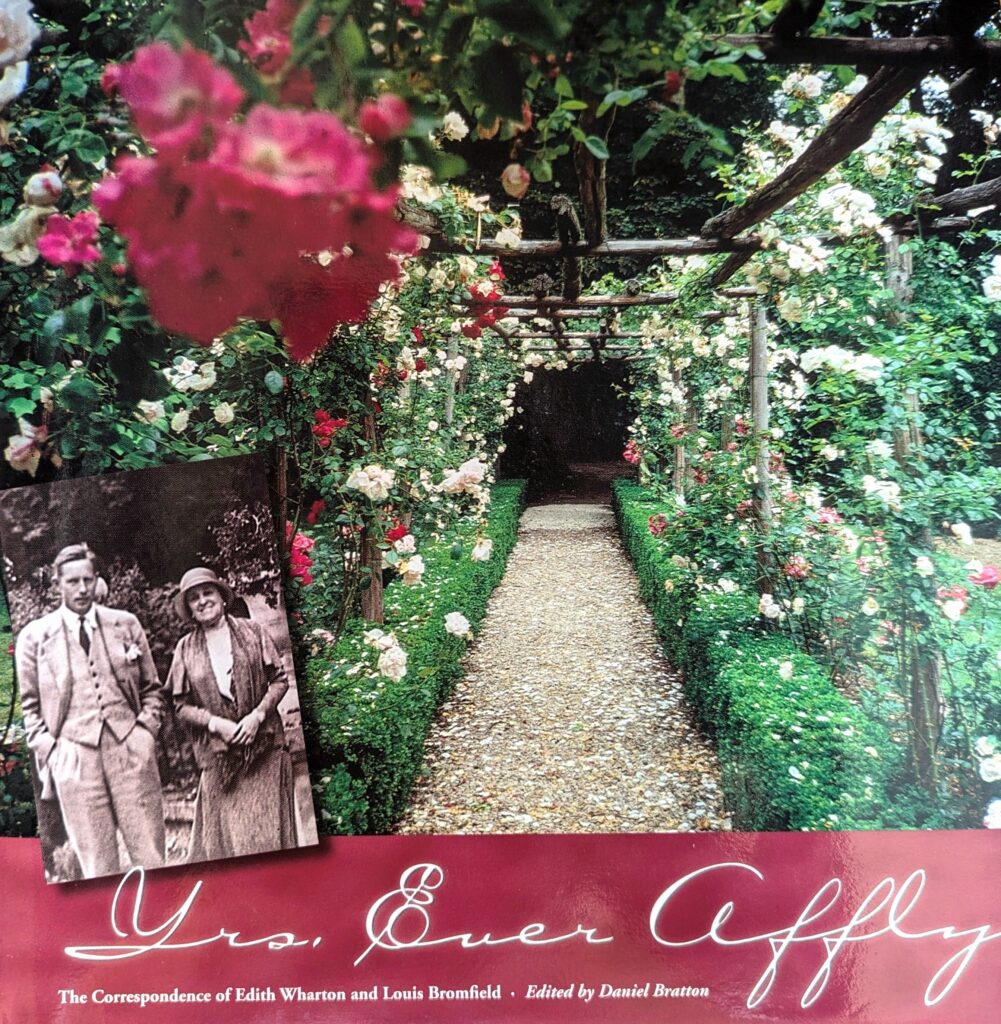

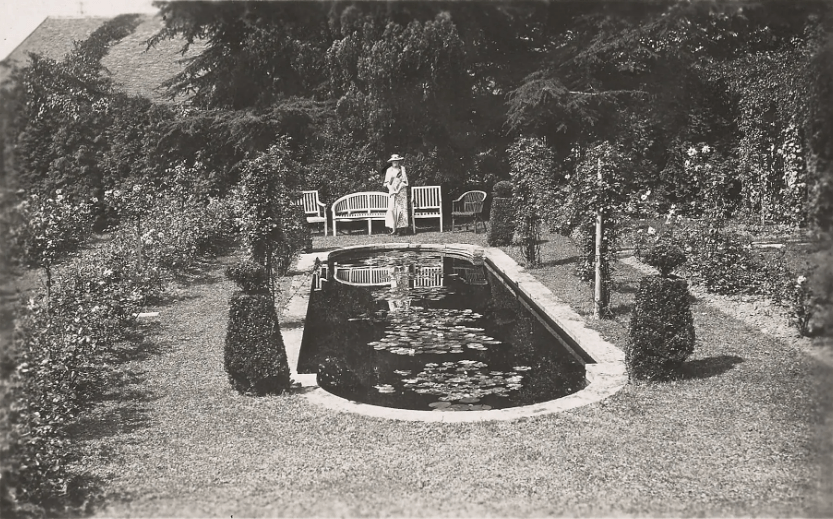

A passionate lover of plant life, Wharton took to young writer Louis Bromfield almost immediately when they first met in 1931. Though Wharton died only six years after that first meeting, and they were separated by over 30 years in age, their friendship was deep and meaningful. They seemed destined to become friends. Their intellect, writing careers, shared friends and acquaintances, and historic estate renovations were just a few of many things they had in common. Their strongest connection, however, was their love of gardens. Most of their letters contain flower, plant, and garden news and interests. They shared in both the delight of Spring’s first blooms and the devastation of an untimely frost.

Bromfield, a native of Ohio, lived for a time on his grandparents’ farm and absorbed the agrarian ideals of Thomas Jefferson. Dropping out of agricultural school at Cornell, he later studied journalism at Columbia. He soon left for France, however, where he served in the Army Ambulance Service on the front lines of World War I. After the war, he moved to New York and pursued a literary career, writing for newspapers and magazines until his first novel, The Green Bay Tree, was published in 1924.

In 1925, he and his wife Mary moved to Paris, where he became acquainted with other American writer expatriates Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway. Five years later, Bromfield and his wife leased the Presbytère St-Etienne, a 16th-century rectory in Senlis, north of Paris. Bromfield renovated the property and established magnificent gardens that became famous among the French locals. Bromfield lived only thirty miles from Wharton’s summer home, Pavillon Colombe, and they became acquainted in 1931.

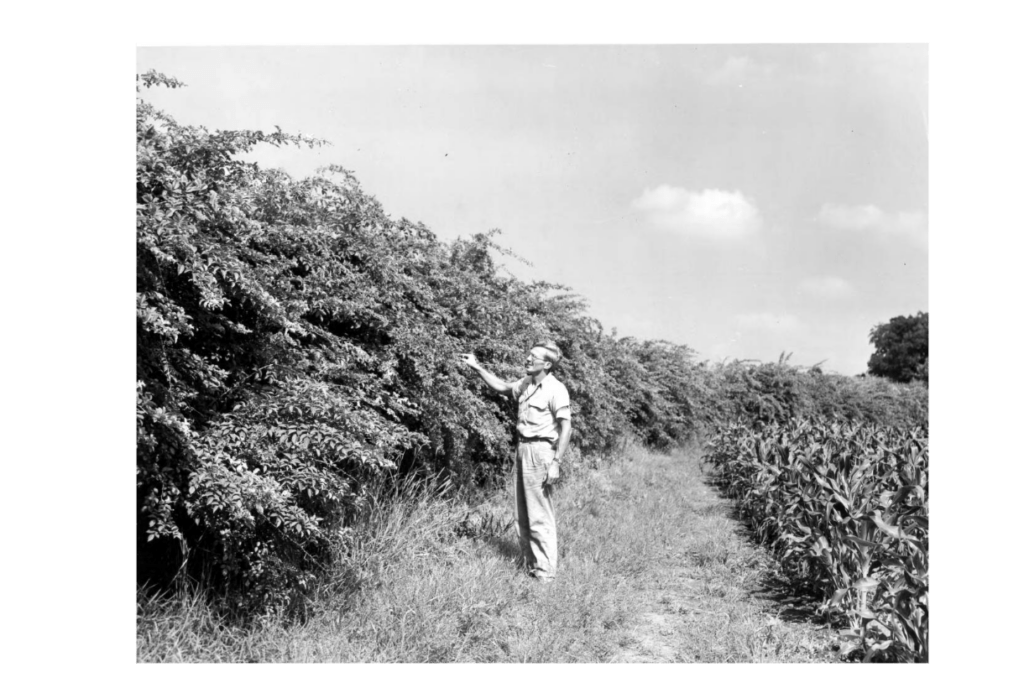

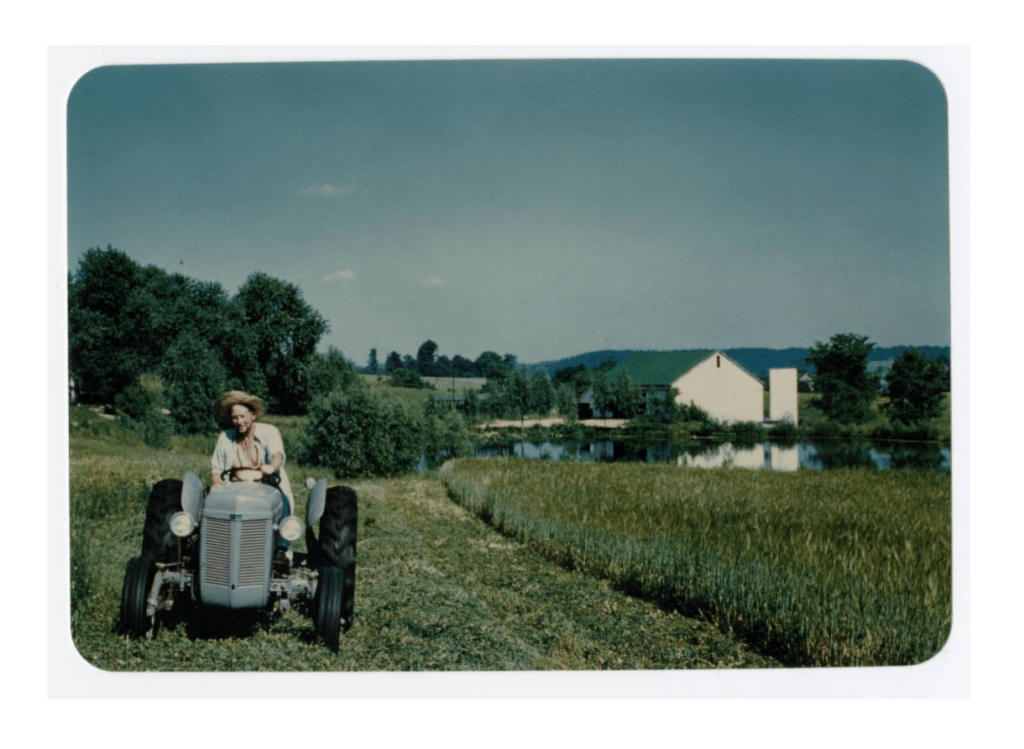

Sensing the upheaval that would become World War II, he moved his family back to Ohio in 1938 (Wharton had died in 1937) and eventually purchased nearly 1000 acres to form Malabar Farm, his vision for community and sustainable agriculture. He spent the remainder of his life advocating for best farming practices and soil conservation while continuing to write novels, plays, short stories, and essays. He published nearly one work per year until his death in 1956.

Upon her death, Bromfield wrote a tribute to Wharton, recollecting that “The bond between us, which was a close bond, as close in many senses as I have ever known, was less that of writing than of gardening….We seldom discussed our writing, but we talked frequently and at great length of our dahlias and petunias, our green peas and our lettuces.”

For more information on Louis Bromfield and Malabar farm, you can visit https://malabarfarm.org/.

Excerpted letter and “A Tribute to Edith Wharton” from Yours Ever Affly: The Correspondence of Edith Wharton and Louis Bromfield, edited by Daniel Bratton.